Neil Gaiman, J.K. Rowling, and What We Take From Flawed Creators

Orson Scott Card. Marion Zimmer Bradley. J.K. Rowling. Neil Gaiman.

This is my litany for the writers of my lifetime who have opened my heart, then broken it.

Orson Scott Card made a passionate argument against xenophobia in his Ender series, then went on a homophobic crusade.

Marion Zimmer Bradley gave the women of Arthurian legend a voice at last in The Mists of Avalon, all while she was abusing her daughter and enabling her husband’s abuse of other children.

J.K. Rowling created a boarding school that we all secretly wanted to attend and made familiar elements like broomsticks and pointed hats magic in a whole new way. Then she poured her significant influence into attacking the rights and dignity of trans people.

And Neil Gaiman brought us deep into the darkness in American Gods and Coraline but always promised a way out at the end. Except the way out for the women he sexually assaulted has not been easy.

[Note: I understand that Neil Gaiman denies these allegations and that he has not been found guilty in the court of law. However, even if one takes HIS version of events as truth, one has to wonder why an older, famous, millionaire repeatedly chose as his sexual partners women who were much younger, less experienced, and, crucially, impoverished. That alone speaks to an abuse of power and a dynamic in which the ability to give true consent is called into question.]

When the creators of art we love act in ways that are abhorrent to us, it doesn’t feel like something we can shrug off with a, “Well, nobody’s perfect.” It feels personal. Is it okay to continue to love their work, knowing the truth of the lives and minds behind it? Is it really possible to separate art and artist? (And is it just me, or are these kinds of scandals particularly rampant among science fiction/fantasy writers? Does anyone know of scandal of a similar scale that has played out upon the giants of other genres?)

For a while, I continued to read OSC although I refused to buy new work by him. Eventually, everything I read by him felt tainted by his homophobia and I gave him up, purging my bookshelf of his work. I came to the same conclusion with Marion Zimmer Bradley and my unread books by her disappeared from my shelf a few months ago. And since most of the Gaiman I read was borrowed anyway, there was nothing for me to purge except a few titles to cross off on my TBR list.

But I’ve been struggling with the question of J.K. Rowling for years. It’s a little ironic, because I was never a die-hard Harry Potter fan. I never stood in line for book releases, attended movies on opening night, or reread ANY of the books in the series. Yet, it was a world I enjoyed when I dipped into it, and one I thought would stand the test of time. It was one I wanted to bring my children into.

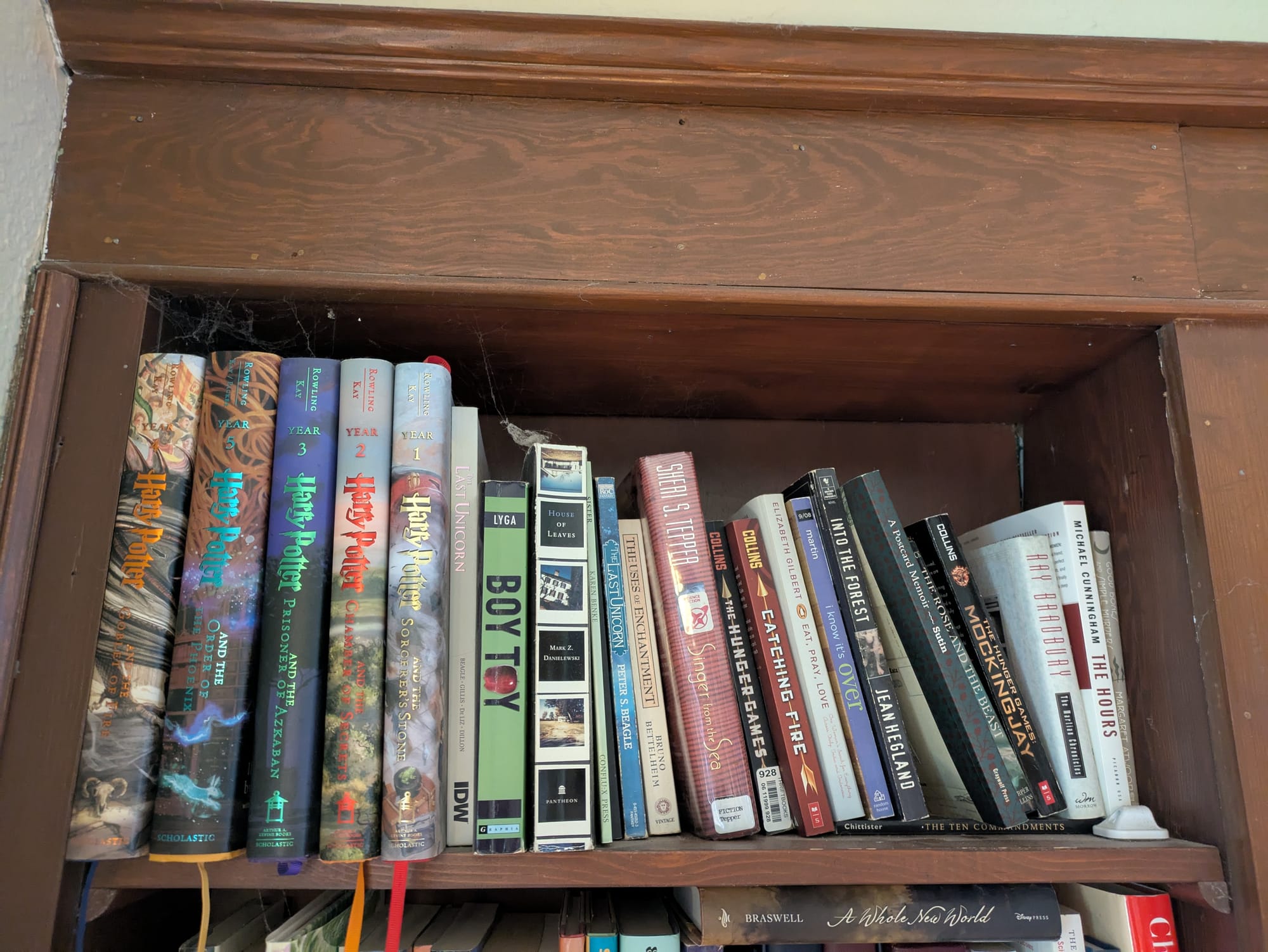

To that end, I’ve been collecting the illustrated volumes of Harry Potter, and I have the first five books in this format. I’ve been saving them to read to my kids when they were old enough, and my older son used to flip through them frequently, looking forward to the day when the whole story would be revealed to him. I was going to start reading them to him when he was six, but then I had a second child and pushed the timeline back to when the younger one was six and the older one was nine. That means we’re set to begin the Harry Potter series, if my kids are still interested, next year.

And of course, in the time between when my son was born and now, J.K. Rowling has tied herself in knots trying to explain how she can be a feminist and also absolutely despise anyone who does not fit her definition of girl or woman.

On NPR, Glen Weldon takes the approach that he will not support any new or future work by the fallen artist; he will no longer support that artist monetarily, but he will allow himself to continue to revisit the work he already owns. This approach seems reasonable, despite the fact that neither J.K. Rowling nor Neil Gaiman will notice the loss of my dollars in their substantial coffers. There is something to be said for bringing your spending habits into alignment with your values—it can be good for you even if it doesn’t significantly “punish” the creator.

I own the first five illustrated Harry Potter books. I will not complete my collection. If I read the entire series to my children, we’ll get the final three from the library or purchase them used. But unfortunately, it won’t end with the books or the movies. New Harry Potter merchandise is appearing on the shelves all the time. And if I introduce my sons to the world, they’ll want to engage with the merchandising, too. And that means I’ll have to have the conversation with them about how J.K. Rowling has become a mouthpiece for hate, and we don’t want to give our money to people who choose to use their power in that way.

Is it even worth it? To point out the hypocrisy of J.K. Rowling’s hate speech against trans people, even as her witches and wizards fight hatred against magicians who do not have “pure” blood? At the same time, is it fair to let her hatred rip to shreds a long-held dream of mine to share this iconic children’s literature with my own kids?

It has me reflecting upon other media I don’t think twice about letting them engage with despite its problematic creators. I read my older son lots of Dr. Seuss even though he often depicted non-White characters in racist ways. I let them listen to “Man in the Mirror” even though Michael Jackson has been accused of molesting children. I won’t forbid them from reading Alice in Wonderland even though there’s quite good evidence that Lewis Carroll was a pedophile.* And I won’t write letters to the school board if Charles Dickens is assigned despite the fact that he was a terrible husband. For all of these dead creators, I am willing to let their work stand on its own and simply avoid the problematic works themselves, not everything they ever created.

Sure, it’s easier to give a pass to dead creators who we can write off as “a product of their time” or who we can argue don’t get any benefit from us consuming their work posthumously, anyway. But I think the sense of betrayal we feel from our modern literary heroes goes a little deeper than the fact that we might, justifiably, hold them to a higher standard.

The act of reading another’s work is actually incredibly intimate, perhaps even moreso when we’re reading a work of fantasy. The author is not just inviting us to empathize with their own lived experiences, but is allowing us entrance into their imagination. Our imaginations are the most secret, invisible, powerful part of our psyches—and when we spend time inside the imagination of a creator, we forge a bond with that creator whether we want to or not. We’ve seen what they’ve pulled up from deep inside of themselves. And we’ve said, “Yes, I trust you to lead me through this place,” or “Yes, I’ve felt this, too!” These books come to mean so much to us because we identify with them. Something in them speaks to something in us; we feel seen; we feel “take care of,” guided through the scary and the grotesque and brought to make meaning of it on the other side. When we find out that the same mind that took us on that journey is capable of justifying unspeakable actions of hatred or abuse, we feel violated. We feel dirty. We were inside that mind, too, and we liked it there. We fear that if we identified with this author’s creation so deeply, perhaps we have the same capacity for darkness and hatred. We trusted them to show us something true and beautiful, and then they showed us something true and ugly about themselves and broke the spell we were relying upon.

Because of this, I don’t believe it IS truly possible to separate the creator from the creation. But I do think it’s possible for deeply flawed humans to create something resonant and beautiful. And I don’t think we are bad people if we believed in that beauty, and want to keep holding onto that beauty, after the rose-colored glasses have been shattered.

As a writer myself, I find myself wondering about the disconnect between the worlds I create on the page, where I have complete control, and the world I create within my own home, when I’m constantly needing to think on my feet and make adjustments on the fly—something that is not my strong suit but that is constantly in demand as a parent of young children. If I write about my highest aspirations for parental love, and someone who reads my work hears me yell at my kids in the yard when we’re running late, does that negate anything of beauty I created? Does it make me a fraud?

Art does not show us what is, but what could be. And our fallen creators remind us, with heartbreaking certainty, that we are not there yet. We have not yet come out of the darkness to the other side. Neither have they.

I still have not made my final decision about Harry Potter. I’ve been having a lot of conversations with other thoughtful fans who are also appalled by J.K. Rowling’s descent into vitriol. But now I know that when and if I do read the Harry Potter books with my kids, I have to be fully prepared to talk about the darkness—real and imagined. And maybe come up with some ideas with them of how we can bring our world closer to the light.

*My sister Krystl Louwagie did some stunning artwork around this question in which she uses Intaglio prints to imagine the emotional reality behind Lewis Carroll’s collection of photos of Alice Liddell. You can view her art here: https://artbykrystl.com/artist-portfolio/. Scroll down to Intaglio Prints and open any of them tagged with, “Lewis Carroll Might be a Jerk.”